The Boogeyman isn’t the most successful Stephen King adaptation out there, but it’s creepy, well-acted, and fun in a sick kind of way. It has one of the most disturbing openings I’ve seen, which I’ll get into below the cut. The film was initially going to go straight to Hulu, but test audiences responded so well (and apparently, Stephen King himself responded so well) that the producers pushed for a theatrical release.

I think this was good call, as the atmosphere and sound design worked really really well in the theater, especially with a few groups of teens shrieking and giggling enthusiastically as the horror unfolded. Nothing makes a horror movie sing like an audience that’s willing to commit.

The Boogeyman is based on the 1973 short story by Stephen King, which was included in his excellent 1978 collection Night Shift, but it goes in some very different directions and adds a lot of complexity to a simple, brutal story.

Dr. Will Harper (Chris Messina) is flailing as a single parent since his wife died in a car crash. His elder daughter, Sadie (Sophie Thatcher), has taken on most of the emotional heavy lifting with his younger daughter, Sawyer (Vivien Lyra Blair) who has developed a debilitating fear of the dark in the wake of their loss. Dr. Harper is a therapist, but refuses to talk to his daughters about his own grief—which could be seen as a protective instinct, but he also shuts down when they try to open up to him, pawning them off on their therapist Dr. Weller (a fabulous LisaGay Hamilton) rather than offering them comfort.

When Lester Billings (the always amazing David Dastmalchian) shows up at Dr. Harper’s home office seeking therapy, but also claiming that a monster murdered his three children, he brings the horror with him and infects their home.

Like a lot of modern horror, this story isn’t really about the monster in the closet—it’s about GRIEF. The main plot of the film starts on the day when the two kids are supposed to go back to school after seemingly about a month of uninterrupted mourning. Their mom’s art supplies and paintings are shut away in her studio—should they pack all that stuff up? Sadie’s BFF has barely talked to her since he funeral, and now she’s running around with a group of “cool” girls who have no patience for Sadie. Sadie’s begun wearing her mother’s clothes, Sawyer can’t be in the dark longer than an eye-blink, and Dr. Harper seems to disappear into an apparently soundproofed room every night rather than being attentive to his kids’ sadness and nightmares.

This movie might be anti-therapy? Or at least anti-therapist—my friend and I were talking about it afterwards and that was finally the only conclusion we could draw. The short story it’s based on has some very strong things to say about the therapist. In the story, Lester Billings is the main character, so this film kind of serves as a continuation of the story—a touch I really liked. But it seems to be mulling the idea that talking about your feelings with friends and family is good and healthy, but that going to therapists might… kill you. And also that if your kids are afraid of the dark it’s because monsters are legitimately trying to eat them.

But that’s a slight tangent—my point is that big capital letter themes like Grief and Trauma and Child Abuse used to be a bit more subtextual in horror, I think. At a certain point it became much more acceptable to bring the subtext to the surface (e.g: Babadook = grief; It Follows’ entity = STDs/sexual trauma) and now we’ve reached a point where the monsters are able to thrive because all the characters say things like “Annie Graham’s sudden obsession with seances is due to her grief” and “Sawyer’s fear of the Boogeyman is her grief over her mother’s death”, so the monsters in Hereditary and The Boogeyman run amok while seemingly wiser heads prevail.

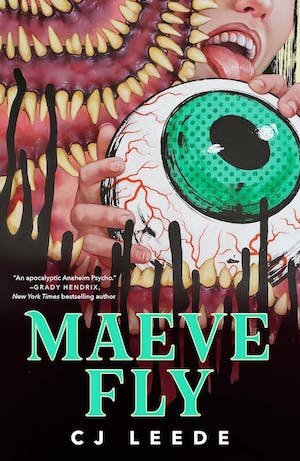

Buy the Book

Maeve Fly

I mentioned child abuse up there, and the other thing I keep thinking about is that The Boogeyman is kind of the anti-Skinamarink. Skinamarink is almost all subtext, and makes its mark by using darkness and long takes to build suspense—which is only occasionally paid off with a concrete shock or jump scare. That movie’s opacity invited a lot of different interpretations. In this house, Sarah Welch-Larson talked about how it reminded her of a childhood fear of the end times. Many others interpreted it as being about child abuse or neglect, as two very young kids are left utterly vulnerable. The Boogeyman starts off with a similar tone.

It opens with a baby being murdered. Not just murdered, but tormented first, as a distorted voice reassures the kid that everything’s all right, and that “Daddy” is here—as the child’s screams become more and more desperate. We don’t see the creature, but we can infer from the child’s terror that it’s not pleasant looking. And then those screams are cut short. And there’s blood splashed on the crib.

Reader, the smile on my face.

I hate gratuitous child endangerment in stories. If a story puts a kid in danger just to squeeze a few more drops of empathy out of me, I tend to root harder for the villain. But in a horror story like this one, the fact that the movie showed it wasn’t afraid to kill a kid set the stakes. Nothing’s off the table—and I love it when nothing’s off the table.

For the first hour or so, the film met my expectations, using deep shadows, creaking closet doors, and half-heard noises to create an atmosphere. Lester Billings’ therapy session is a setpiece of fantastic slow burn dread; its aftermath is genuinely upsetting. I mentioned the sound and set design up in my opening paragraph—one of the greatest choices in the film is how it uses Sadie and Sawyer’s responses to grief. Sadie tries to drown out the world with music, and for the rest of the film many of her interactions with the monster focus on hearing weird noises, being swallowed up by eerie silences, or, in a few cases, having to cope with terrifying loud explosions. Sawyer deals with her fear of the dark by surrounding herself with different lights: she has an endless supply of Christmas lights and neon signs strung up in her room, and she sleeps with a glowing, moon-like globe pressed to her chest. In a very effective running scare, she rolls the globe into dark corners to try to convince herself there’s nothing there. This does not always work.

I kept thinking of Skinamarink—where the children in that film are truly, utterly, helpless, The Boogeyman finds a balance between showing us how resourceful and clever Sawyer is, but also reminding us that she’s outmatched. But here, too, as the film goes along a lot of the atmosphere is sacrificed to people theorizing about the monster, making plans to fight it. I found myself in the same dilemma I wrote about after Evil Dead Rise and the latest Hellraiser reboot: once I’m invested in the characters, it gets harder and harder to enjoy watching them suffer—which kind of undercuts the fun of horror.

There are also points when the film recalls IT in its attempts to create a mythology around the monster, which, again, I think is a bit of an overreach. A movie like The Boogeyman should lean into the darkness itself, the terror of not knowing if something is lurking in the shadows. Where in IT the worldbuilding around Pennywise add to the cyclical nature of the attacks on Derry, and make the whole story more epic, here I think it would be a lot scarier if the monster remained mostly unseen and inexplicable. Having said that, the glimpses of the monster are pretty creepy, and part of me was happy to relax and root for Sadie to figure out how to fight back, even as another part of me wished the movie maintained the nihilism and spookiness of that opening scene through to the end.

Leah Schnelbach wants one of those moon lights. Come join them in the haunted therapy session that is Twitter!